Persecution and the suffering church – synchroblog

Ovamboland, Namibia

On Sunday 30 January 1972 the congregation of St Luke’s Anglican Church, Epinga, was coming out of church after Mass. Epinga is about 30 miles east of Odibo, where the main Anglican Church in Ovamboland is situated. While going from the church, members of the congregation were accosted by a police patrol, and were told they were not to attend any meetings. They scattered into the bush, and then when the police vehicles had departed, they came back together again asking what it was all about when police on foot surrounded them.

They were searched for weapons and one young boy aged about 18 was carrying a walking stick. The chief of the police began poking a stick into his face and shouting at him. The boy lifted up his arms to ward off the blow, whereupon the policeman shot him through the head. The whole patrol then opened fire, and shot at him until his skull was a bloody pulp. Seeing this the congregation fled, and several of them were shot as well. Four died instantly, and another is said to have died later in hospital.

Those who died are: Thomas Mueshihange, Benjamin Herman, Lukas Veiko, Mathias Ohainenga. The wounded were Seimba Musika, Phillipus Katilipa and Kakaimbe Hidunua. The parish priest still had some fragments of the skull of the boy who was first shot in the vestry of the church. In the early church too, it was the custom to bury the bones of the martyrs who had died for Christ under the altar of the church, and to erect churches on the tombs of the martyrs.

At the inquest into the deaths, the police said they had been attacked by a group of 100 Ovambo armed with axes, pangas, bows and arrows (the Rector of the parish said they were armed with Bibles, prayer books and hymn books). The police also said that after making “exhaustive inquiries” they had been unable to identify any of the dead except Benjamin Herman. Almost all the affidavits at the inquest were from the police, and those of non-police witnesses (who were wounded) attest to the fact that the congregation was not armed. The inquest magistrate found that the police had opened fire “in the execution of their duty”.

The Archdeacon of Ovamboland compiled a list of the names of the dead and wounded, together with their next-of-kin (the spelling of the names above may not be correct, as they were transmitted orally, by telephone).

The circumstances

The Rector of St Luke’s, Epinga was the Revd Stephen Shimbode The Archdeacon of Odibo was the Ven Philip Shilongo, of St Mary’s, Odibo. The Archdeacon of Ovamboland was the Ven Lazarus Haukongo, who had been Rector of the Parish of Holy Cross, Onamunama, which was close to Epinga. Most of the Anglican parishes in Ovamboland were among Kwanyama-speaking people, and were stretched out eastwards from Odibo along the border with Anglola, at intervals of about 10 kilometres.

Kwanyama-speaking people lived on both sides of the border, and many Anglicans lived to the north, in Angola, and until this time the crossed the border to attend church services. Most of the church buildings were no more than half a kilometre from the border fence.

A short time before this incident the South African government had declared a state of emergency in Ovamboland, which prohibited meetings. There was no time for news of this proclamation to have reached ordinary churchgoers in Ovamboland, so the members of the

congregation were almost certainly not aware of it.

There are various possible conclusions that one can draw from the inquest.

One is that the magistrate was either under the control of, or intimidated by the police, and saw it as his duty to exonerate them no matter what, and that he therefore either did not either ask for or consider evidence from all sides, and that the verdict was therefore a cover-up.

Another is that the magistrate was aware of what had happened, and that he considered that it was the duty of the police to shoot church congregations.

The brief report above was one that I compiled shortly after the events described, which were one of my closest encounters with persecution in which people were actually killed. A month after that I was deported from Namibia, along with the bishop, Colin Winter, the diocesan secretary, David de Beer, and a teacher, Toni Halberstadt.

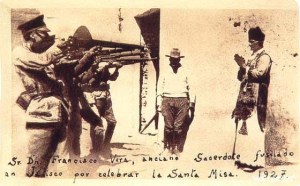

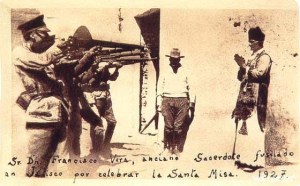

No, it didn’t quite happen like this in Ovamboland, this picture was taken in Mexico. But the circumstances are similar. If the people who died at Epinga had not gone to Mass, they might still be alive today. For the Mexican story, read “The power and the Glory” by Graham Greene.

I thought the story of the Epinga martyrs deserved to be told, but the Anglican Church in Southern Africa was strangely reluctant to hear the story of its own martyrs. It honoured contemporary martyrs in Uganda, such as Yona Kanamuzeyi, in the church calendar, but not its own martys in Epinga. It dishonoured those who were imprisoned for their faith in South Africa and Namibia and other places by removing the feast of St Peter’s Chains (August 1) from the church calendar. So I thought I should tell their story here.

And since a blog is a journal of sorts, I reproduce my journal for 28 February 1972, which was the day on which I first heard of the events at Epinga a month earlier. It was my last official duty in the Anglican Diocese of Damaraland (as the Diocese of Namibia was then known) — to represent the Anglican bishop, Colin Winter, at the uniting synod of two Lutheran Churches in Namibia — the Evangelical Lutheran Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Ovambokavango Church. We had received our deportation orders over the weekend, so the bishop was unable to attend himself. And deportation was itself persecution of a sort.

Monday, 28 February 1972

Early in the morning I went to the bishop’s house to fetch Philip Shilongo and Erica Murray to go to the Lutheran Synod at Otjimbingue. Erica came out alone, and said Fr Philip had not returned home last night, and said she thought he had been going round Katutura getting up a petition for the removal of the dean. We drove past Katutura to go to Abraham Hangula’s new house, but we found Fr Philip walking down the road, and he got in the car and came with us.

We were driving in the blue Combi, and refuelled at Okahandja, and got some road maps for Erica so she could see where we were going. We arrived about 10:00, and went and talked to Pastor Wessler. The bishop wanted us to discuss the whole situation in Ovamboland with the aim of issuing a joint statement on it, as Nangutuuala had asked him to do. Unfortunately the Ovambo delegates to the synod had not yet arrived, so we could only meet with the Evangelical Lutheran Church people.

Fr Philip told us what had happened at Epinga on January 30th at Fr Shimbode’s church, St Luke’s. He said that after Mass that Sunday, at about 1:00 in the afternoon, the congregation was coming out of the church, and a patrol, whether of police or army he could not find out, told the people coming out of church that they were not to hold any meetings. The congregation scattered into the bush, and when the lorries had driven off, they came together and began to discuss the incident, and asked each other what it was all about. Then the patrol surrounded them, and searched them for weapons. One boy, aged about 18, had a walking stick, and the leader of the patrol began shouting at him, and poked a stick in his face. The boy lifted his arms to ward off the stick, and the captain shot him with his revolver. Then the whole patrol opened fire, and shot his head to pieces. The congregation scattered again, and three of them were shot dead, and two or three more seriously wounded. One of the injured ones died later in hospital. One of the others had serious brain injuries, and they did not expect him to recover. Fr Shimbode still had some of the bones from the shattered skull of the boy who was shot first in the vestry of the church.

So lie in honour the bones of the martyrs who by the blood of their necks have borne

witness to Jesus, and to their faith in the kingdom of God; they shall shine like stars and move like sparks through the stubble, and their Lord will receive them with honour in his kingdom.

Some of the Paulinum students, who had worked at the Oshakati hospital during the vac, testified to the admission of people from that area who had been shot, and the numbers tallied. They also knew of others who had been shot on other occasions, but we did not know why, or the circumstances of the shootings.

We had lunch with the students and I met Miss Voipio, who wrote the booklet about the contract system. After lunch we returned for more discussions, and then had tea with Pastor Sundermeier and Pastor Kaipianen and Miss Voipio. Dr Sundermeier was now teaching at Mphumulo in South Africa, but had come up for the synod where the two Lutheran churches were uniting. After tea I phoned the Daily Mail, and had great difficulty in getting through, the dictate typist told me to hang on, and then cut me off, and then after three minutes I began to dictate the story, what Fr Philip had told us. I had just got to the part where I said “four people were shot dead” when we were cut off. I rang the operator at Karibib, and she said Windhoek had cut us off — there was a strict limit on trunk calls of six minutes, and there was nothing she could do about it. I had visions of what might happen with half a story like that going around, and told her it was a very important call, and did an excited Smitty act with her, but it made no difference. Later I talked to Father Kangootui, who had also come for the synod, and told him about our deportation.

The synod followed, and the opening session was a service, with a sermon preached by Habelgaarn, the guy from the Lutheran Church in South Africa. Bishop Auala presided over the first session of the synod then, which was greetings from other bodies and churches, and I represented the bishop in bringing the greetings of the Anglican Church.

Afterwards I met the combined church board with Fr Philip, and told them again what we knew of the situation in Ovamboland, but the Ovamboland people — bishop Auala and company, were stalling. They were sympathetic, but not interested. We went on till after 11:00, and there was no conclusion. Afterwards Pastor Maasdorp and Pastor Rieh came and apologised to me for the meeting, and both seemed terribly embarrassed by the prevarication of the delegates from the Ovambokavango Church. They felt they had let us down, but it wasn’t their fault at all. Then Pastor Diehl also came and apologised, and he too was embarrased by it all. Two delegates from the German Lutheran Church had earlier expressed support for us in the action we were taking against Dahlmann. We drove back to Windhoek, and after we reached the tar at Wilhelmstal, I stopped to let Erica take over. I went to sleep in the back, and Fr Philip acted as kudu observer, and there were many kudus on the road, all bent on suicide. We got back to Windhoek after 2:00 am, and I drove the Combi back to the hostel, feeling dead beat.

Some explanatory notes:

- Daily Mail – I was a stringer (correspondent) for the South African Morning Group of Newspapers, and so regularly sent news reports to them. But the story of the Epinga martyrs was never published, except for the distorted account of the inquest. That is one reason why I thought it should be told here.

- Smitty – was J.M. Smith, one of the craziest journalists in Namibia, whose legendary encounters with the Namibian telephone system were repeated years afterwards.

- Dahlmann – another journalist, Kurt Dahlmann, editor of the Allgemeine Zeitung, who had been a Luftwaffe pilot in World War II. The Allgemine Zeitung under his editorship was an ultra-rightwing, almost neo-Nazi paper, which had recently published several slanders against Christian leaders in Namibia.

This post is part of a synchroblog, in which several bloggers blog on the same topic on the same day. In this case the topic is “Persecution and the suffering church”. Below are links to the other blogs with posts on this topic.

Posted in

Anglican,

church history,

history,

Namibia and tagged

African Christianity,

Anglican Communion,

Anglicanism,

apartheid,

Church and State,

church history,

Colin Winter,

martyrdom,

martyrs,

Namibia,

persecution,

Security Police,

South Africa,

synchroblog