Boneland by Alan Garner

Boneland by Alan Garner

Boneland by Alan Garner

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

It is almost impossible to say anything about this book without spoilers, so I hope that anyone who reads this has already read the book.

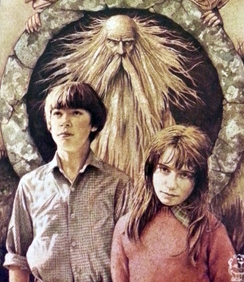

It is a sequel to The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath. In those books twelve-year-old Colin and Susan go to stay on a farm near Alderley Edge in Cheshire, England, and discover that the Edge is haunted by all kinds of strange creatures, malicious goblins, suspicious fairies and elves and the like, and there is a strange woman, a witch, who seems to have evil designs on them, and especially a stone that Susan had inherited.

Some of the creatures, good and evil, that they encounter are from local folklore, and others from stories from further afield. Eventually the children overcome the forces of evil, and are left in peace for a while.

Some of the creatures, good and evil, that they encounter are from local folklore, and others from stories from further afield. Eventually the children overcome the forces of evil, and are left in peace for a while.

Boneland is set much further in the future, where Colin has grown up and become a professor of astrophysics.

One problem that Professor Colin Whisterfield has is that though he has an exceptionally good memory, he can remember very little of his childhood before he was 13.

He works at the Jodrell Bank radio telescope, and spends much of his time at work trying to find a twin sister that he thought he had, whom he believes has vanished into the Pleiades, riding on a horse. He has a bad conscience about wasting his employers’ time on this personal project, and so at one point he resigns, but his resignation is not accepted.

He is also worried about his missing sister, whom he can hardly remember, and thinks he might be going mad, so he visits a psychotherapist, Meg, She tries to probe his memories, but there are some places in his past where he both wants to go and fears to go.

It is impossible to go beyond this point without spoilers, so if you’ve read the book and want to go further, see my original review on GoodReads. See also my review of The Weirdstone of Brisingamen.

If you have read any of these books and written a review of any of them in a blog or elsewhere, please leave a link to your review in the comments below.